TLS Certificates 101

Over the last couple years I’ve been involved in many projects that require TLS certificates and some other technologies to provide security and establish encryption in transit for network communications. These technologies involve different concepts, protocols and standards such as mTLS, X509, PKI, digital signatures, hmac, symmetric and asymmetric encryption, different cryptographic algorithms etc and can feel very overwhelming especially for people that are new in the topic.

I decided to write a quick blog post and share some of the lessons I’ve learned over the years. It is my intention to provide some guidance to newcomers when it comes to debugging these kinds of issues.

I don’t consider myself an expert in the whole TLS topic (I’m not a Cryptographer), however I’ve spent considerable time on this to the point that I feel very confident when debugging most issues related to TLS.

I firmly believe an expert is a person who has made so many errors and mistakes in the past and because of that he has accumulated so much knowledge to the point that he knows almost all the answers. I still need to make more 😉

Having said that, let’s start our journey into the TLS world.

What is TLS?

TLS, short for Transport Layer Security, is a cryptographic protocol designed to provide communications security over a computer network.

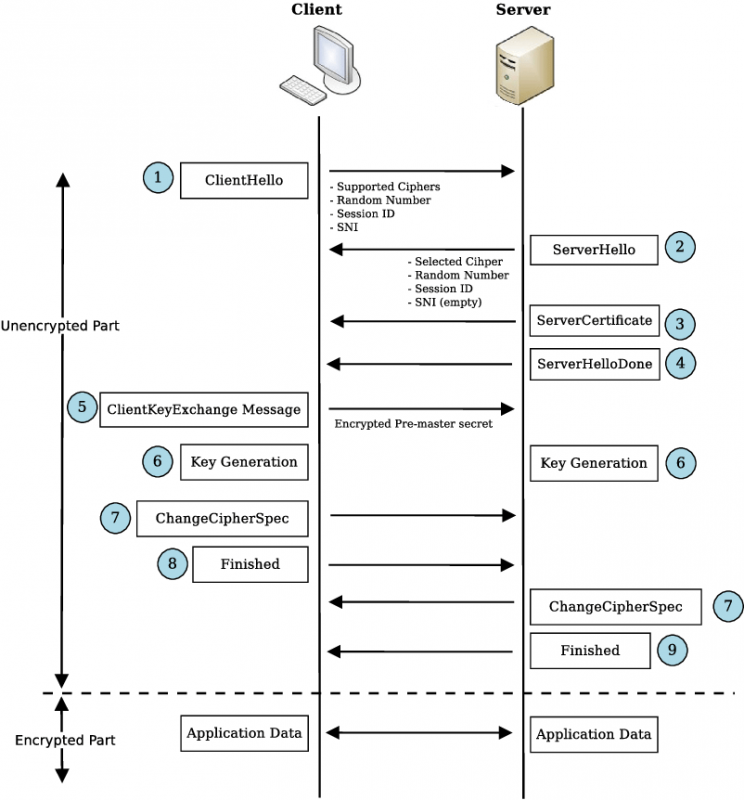

The TLS protocol is a complex piece of engineering with many security mechanisms and moving parts used to achieve security of data in transit by combining symmetric and asymmetric encryption techniques, if you want to learn more details about this technology I highly recommend to look at the TLS Wikipedia page, also here is an awesome diagram by Wazen Shbair that shows the different steps that happen during the TLS handshake process such as choosing a cipher suite or exchanging a shared key.

There are many different versions for this protocol but for practical purposes the only thing you need to know is:

- TLS 1.0 and TLS 1.1 are known to be very vulnerable so you should never use them

- TLS 1.2 is considered to be much more secure and is recommended to use

- TLS 1.3 is an improved version of TLS 1.2 in terms of performance

What are TLS Certificates?

Excellent, now that you know TLS is the technology behind TLS certificates you may be wondering, what are TLS certificates?.

A TLS certificate is an implementation of a X509 Certificate, X509 is a standard that defines the file format used to store information related to an entity (among other things). This is very important because the main purpose of a certificate is to provide an identity to an entity, an entity can be anything, such as a website domain, a server, a piece of software, a workstation, a laptop or even a person. Similar to real life, people (entities) have birth certificates and driver’s licenses that prove who they are, this documents are backed up by government institution that we all trust (well … kinda), if you ask someone to prove their identity that person will probably show you their ID and if the ID looks damaged or you think there’s something phishy you can ask for additional forms of identification until you are convinced that you can trust them.

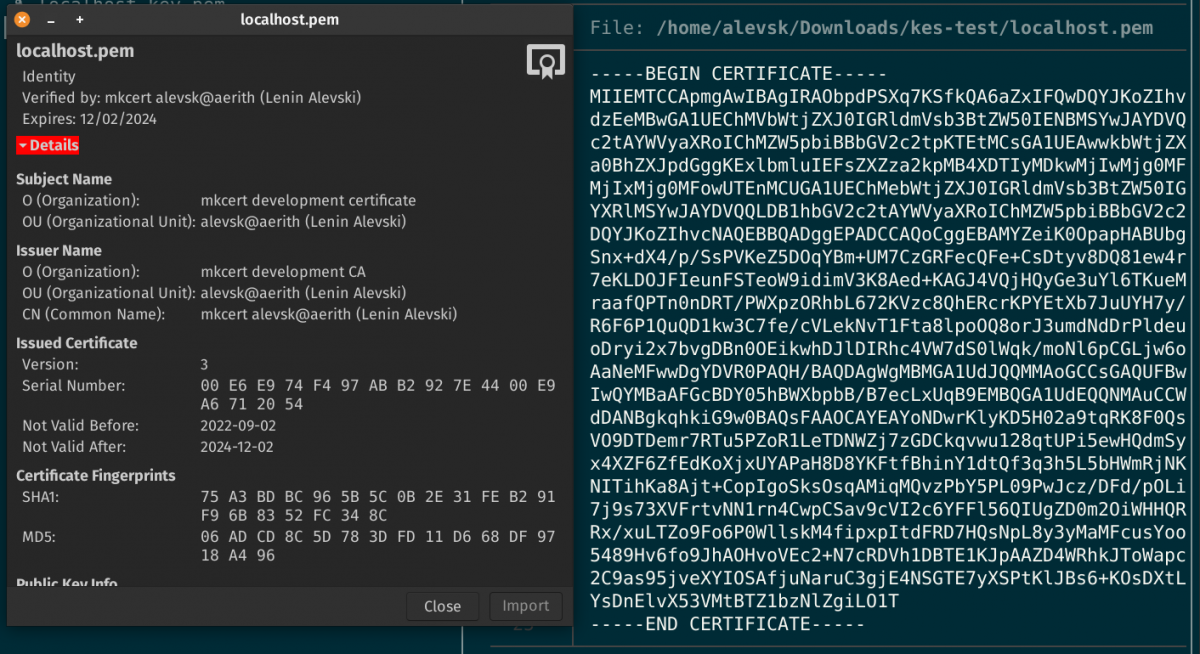

A TLS certificate will looks like this:

The TLS certificate contains many different fields like:

- Subject name: the entity name, person name, website domain, etc

- Issuer name: the authority that issued the certificate

- Period of validity: the certificate is not valid before or after this dates

- Additional cryptographic information and digital signatures

When an application (like your web browser) connects to a website by typing the IP address or the domain, ie: www.alevsk.com, the server behind will return a TLS certificate, the browser will then look at it and decide what to do next (exchange keys and establish a secure connection) based on the fields above.

As you can see, it is the client’s responsibility to verify these TLS certificates, the server may offer a perfectly fine certificate and the client could still choose to throw it away. With that said, I decided to write this blog post to share my experience debugging server applications during countless hours just to find the issue was on the client side or in the certificate itself, customers will swear the server is broken and not working when in reality it was their client not trusting the certificate authority or the clock their was misconfigured.

But before doing that I want to show you a couple of examples of TLS certificates being used on some applications, for that I have prepared a couple of code snippets.

Suppose you are running a simple web server written in go like this.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"net/http"

)

func hello(w http.ResponseWriter, req *http.Request) {

secret := req.URL.Query().Get("secret")

fmt.Fprintf(w, fmt.Sprintf("pong %s\n", secret))

}

func main() {

address := "0.0.0.0:8080"

http.HandleFunc("/ping", hello)

fmt.Println("Starting server on", address)

if err := http.ListenAndServe(address, nil); err != nil {

return

}

}

Let’s query the server running on port 8080 via CURL.

curl http://localhost:8080/ping\?secret\=eaeae

pong eaeae

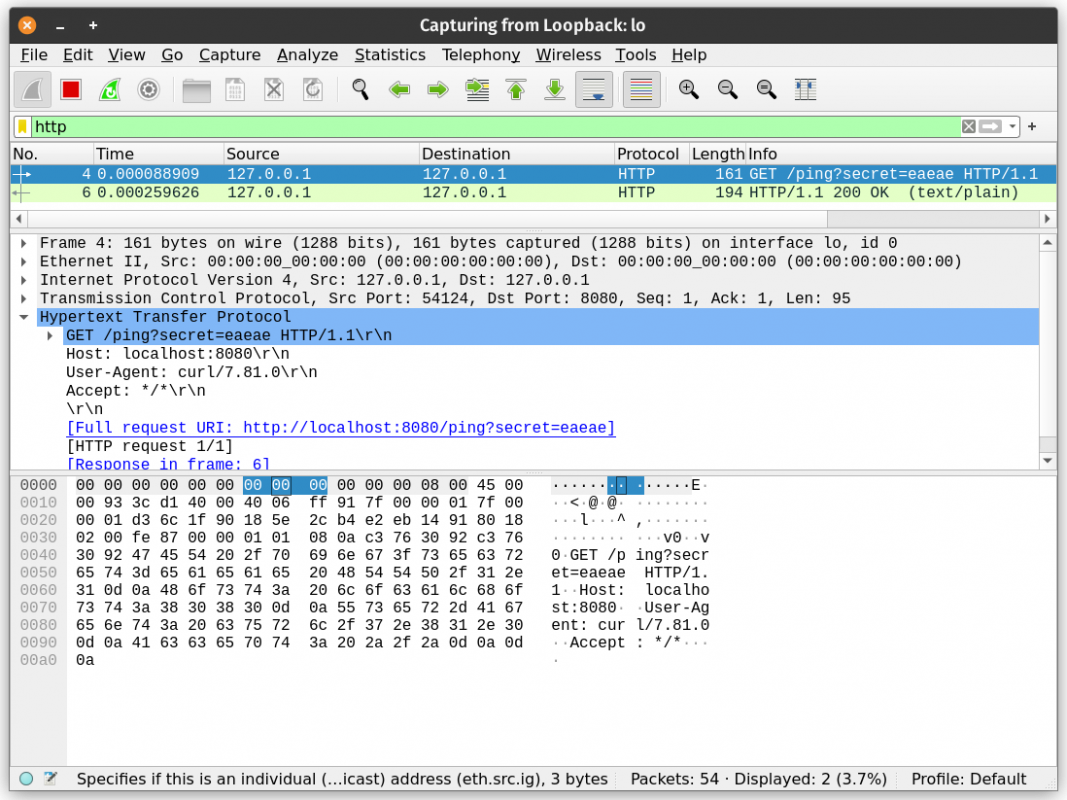

With curl I’m performing a GET request and the server is replying fine, notice how I’m passing a secret via the secret parameter in the URL, everything looks good so far but there’s a problem.

This is an insecure web server, hence all the traffic going from the client (curl command) to the server (Go application) can be captured and the secret can be retrieved in plain text.

Let’s fix this by adding a TLS certificate to this web server, but first, how do we get one? Well, there are two types of certificates: self-signed certificates and certificates issued/signed by a certificate authority.

A certificate authority is an entity that stores, signs, and issues digital certificates. Going back to the society metaphor, it will be the equivalent to a government institution that many people trust.

- Self-signed certificate: ID document that you crafted yourself and its not valid

- Certificate signed by a certificate authority: birth certificate, drivers license or ID document that is backed up by the government institution

- Certificate authority: The government institution that most people trust by default

Using a TLS certificate signed by a certificate authority has many advantages that I’m going to discuss in some other blog post, for now it’s enough to say that you have to pay in most cases to get one of those but it’s worth it. Now let’s generate some certificates.

Tools for playing with TLS certificates

I’ll focus on self-signed certificates for this example and I’m going to show you how to generate them using three different tools.

Mkcert

Mkcert is a tool created by Filippo Valsorda. Mkcert is a simple zero-config tool to make locally trusted development certificates with any names you’d like, you can download it and installed following the instructions directly from this Github repository https://github.com/FiloSottile/mkcert

mkcert "localhost"

#Created a new certificate valid for the following names 📜

# - "localhost"

#The certificate is at "./localhost.pem" and the key at #"./localhost-key.pem" ✅

#It will expire on 14 December 2024 🗓

Certgen

Certgen is a tool created by MinIO, the startup I currently work with. Certgen is a dead simple tool to generate self signed certificates, you can download it and installed following the instructions directly from this Github repository https://github.com/minio/certgen

certgen --host localhost

#2022/09/14 21:58:54 wrote public.crt

#2022/09/14 21:58:54 wrote private.key

OpenSSL

OpenSSL is a tool that doesn’t require any introduction, it has been part of the TLS arsenal of system administrators and network engineers for decades, if you wish to use openssl to generate certificates the process is a little bit more manual than with the tools above but still is fairly simple to use.

openssl genrsa -out private.key 2048

cat >> certificate.cnf << 'END'

[req]

distinguished_name = req_distinguished_name

req_extensions = req_ext

prompt = no

[req_distinguished_name]

O = "http-server"

C = US

CN = "localhost"

[req_ext]

subjectAltName = @alt_names

[alt_names]

DNS.1 = localhost

END

openssl req -new -config certificate.cnf -key private.key -out certificate.csr

openssl x509 -signkey private.key -in certificate.csr -req -days 365 -out public.crt

#Certificate request self-signature ok

#subject=O = http-server, C = US, CN = localhost

Doesn’t really matter which tools you use to get your certificates as long as they are not malformed. Going back to our Go code I made a couple of changes and the code looks like this now.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"net/http"

)

func helloTLS(w http.ResponseWriter, req *http.Request) {

secret := req.URL.Query().Get("secret")

fmt.Fprintf(w, fmt.Sprintf("pong %s\n", secret))

}

func main() {

address := "0.0.0.0:8080"

http.HandleFunc("/ping", helloTLS)

fmt.Println("Starting server on", address)

if err := http.ListenAndServeTLS(address, "public.crt", "private.key", nil); err != nil {

return

}

}

The most relevant change is that I’m using the function http.ListenAndServeTLS now which is pretty explanatory. This function allows me to pass two files: the TLS certificate (also called the public key) and the corresponding private key. As mentioned before the TLS certificate contains information about the expiration date, valid domains, digital signature, certificate authority, among other, that will be relevant to the client while the private key will remain secret in the server and be used by the Go application to decrypt encrypted messages sent by the client during the TLS handshake. If you want to learn more about Public Key Cryptography I highly recommend looking at the PKI Wikipedia page.

I’ll run the Go program again and this time I’ll use the https protocol in the curl command.

curl https://localhost:8080/ping\?secret\=eaeae -k

pong eaeae

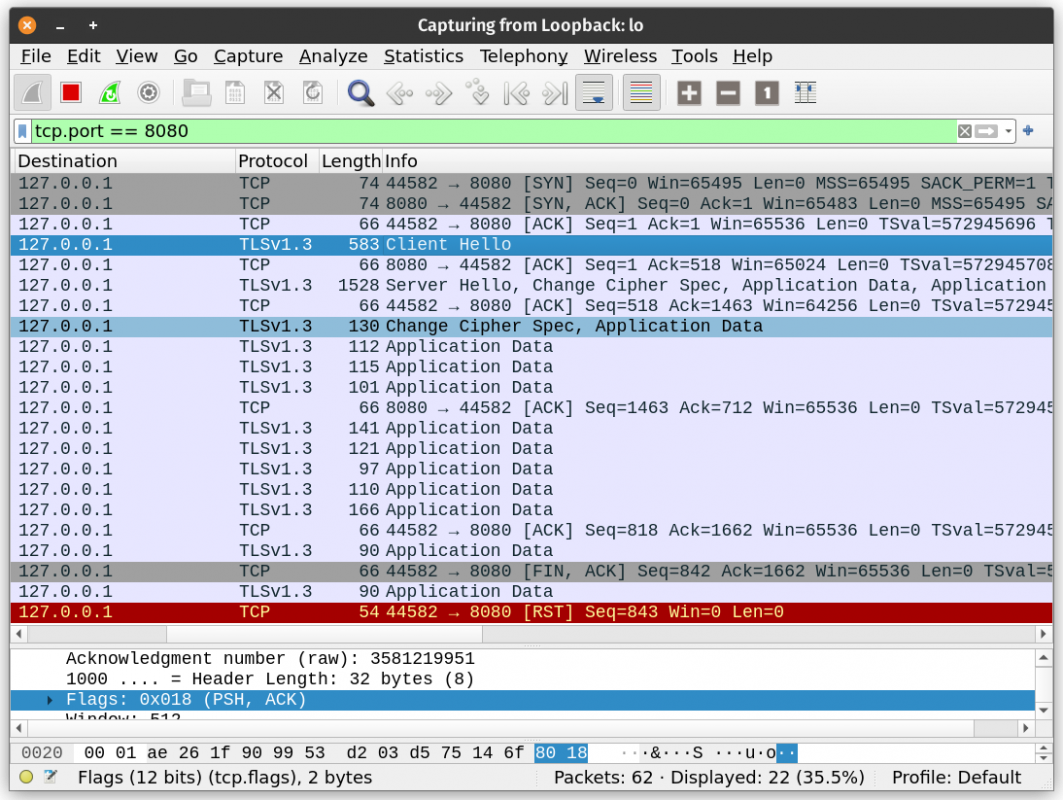

Before continuing I have to mention, just for the sake of the example and to demonstrate how TLS is securing the communication, I’ve included the -k flag in the curl command, passing this flag will make curl disable all TLS verifications. If you inspect the traffic on wireshark this time you’ll only see the TLS handshake and encrypted data after that, no more parameters in plain text.

If you are not able to inspect SSL/TLS traffic in wireshark try adding the custom server port under Edit -> Preferences -> Protocols -> HTTP -> SSL/TLS Ports. You can add your custom port, ie: 8080. Change it to: 443,8080.

Debugging TLS certificate issues

Now comes the fun part, and where I’ve “invested" countless hours trying to fix other people’s problems, debugging TLS certificates issues.

If I go back and remove the -k flag from my curl command I get the following output.

curl https://localhost:8080/ping\?secret\=eaeae

#curl: (60) SSL certificate problem: self-signed certificate

#More details here: https://curl.se/docs/sslcerts.html

#curl failed to verify the legitimacy of the server and therefore could not

#establish a secure connection to it. To learn more about this situation and

#how to fix it, please visit the web page mentioned above.

The error message is pretty clear, curl is failing to verify the certificate because this is a self-signed certificate, meaning it cannot be trusted. How does curl know this is a self-signed certificate?

Well it is very simple, remember when I said there were only two types of certificates?

There are two fields in the certificate: Subject Name and Issuer Name, if both fields match then this is a self-signed certificate. If they don’t then this is a certificate issued/signed by a certificate authority, that may or may not be trusted by the client.

The solution for this is quite simple, in your client application use the same certificate itself to verify its authenticity, since the certificate is technically its own authority, with curl you need to include the –cacert flag and specify the path to the public.crt used by the server.

curl https://localhost:8080/ping\?secret\=eaeae --cacert public.crt

pong eaeae

The above is one of the most common TLS issues I’ve encountered in the past few years and I hope I did a good job explaining the root cause, how to approach the problem and finally how to find a solution.

Next is a list of the most common TLS issues I’ve seen and some advices on how to debug them:

| TLS Error | Debugging advice |

|---|---|

| SSL certificate problem: self-signed certificate | Ask people to provide you with the public key of the server (or download it yourself with openssl, ie:echo |

| SSL certificate problem: unable to get local issuer certificate | Update ca certificates in the client machine (sudo update-ca-certificates) or ask for theca.crt(certificate authority certificate) and pass it with the–cacertflag in the curl command |

| X.509 Certificate Signed by Unknown Authority | Client doesn’t trust the certificate authority that issued the certificate, if you have the ca.crt files you can use openssl to verify the chain of trust:openssl verify -verbose -CAfile root.pem -untrusted intermediate.pem server.pem |

| SSL: no alternative certificate subject name matches target host name’XXXX' | The certificate used by the server is not valid for any of the domains the client is trying to use to connect, are you using an IP address instead of a domain name? Check the whole list of domains inside the certificate and make sure they match to what you are using in your curl command |

| SSL certificate problem: certificate has expired | Make sure the client and server clocks and correctly configured and in sync |

| SSL certificate problem: certificate is not yet valid | Make sure the client and server clocks and correctly configured and in sync |

| SSL: certificate subject name’XXXX’does not match target host nameYYYY | The certificate used by the server is not valid for any of the domains the client is trying to use to connect, are you using an IP address instead of a domain name? Check the whole list of domains inside the certificate and make sure they match to what you are using in your curl command |

| Public key certificate and private key doesn’t match | Pretty explanatory, I’ve seen this happening mostly when people copy a bunch of keypairs around and get confused, you can use openssl to verify this |

| Connection error:The SSL connection could not be established, see inner exception.. | Check which version of TLS is the client using, most probably is using an old vulnerable version like 1.0 or 1.1, you need to upgrade your client TLS version to TLS 1.2 or above.Test this using:curl --tls-max 1.0 https:// |

As I remember more errors and ways of how I approach the problem to find a solution I may add them to the list, most of the errors are very explanatory but for some reason users struggle with them, when it comes to TLS errors they may think it’s some kind of obscure or arcane technology but its not.

Takeaway

As I said before, I’ve spent countless hours debugging this kind of issues, my main advice will be: instead of jumping directly into pulling server/application logs first look as the client side, always use the curl command first for testing, if the customer provide you with some client certificates for mTLS authentication or a ca.crt file and you are not even make them work with curl then definitely the issue is in the client side and not in your application.

- Pay attention to how the client is referencing the server application, what domain the client is using in the curl command?

- Make sure the client and server clocks and correctly configured and in sync

- If the certificate contains wildcards make sure those are valid for the domain the server is using and the client is referencing

- Make sure the public key and the private key matches, you can use OpenSSL to verify this

Here are some useful TLS certificates debugging tools I use:

- https://www.sslchecker.com/certdecoder

- https://www.sslshopper.com/certificate-decoder.html

- https://www.sslshopper.com/csr-decoder.html

- https://certlogik.com/decoder/

- https://www.ssllabs.com/ssltest/analyze.html

Happy hacking