Bug Bounties vs. Enterprise Security: The Disconnect

Disclaimer

First, I want to clarify that the opinions expressed here are mine alone, based on my own personal biases and observations. They do not represent the opinions of my current or former employers, and I am not speaking on behalf of any official authority.

Motivation

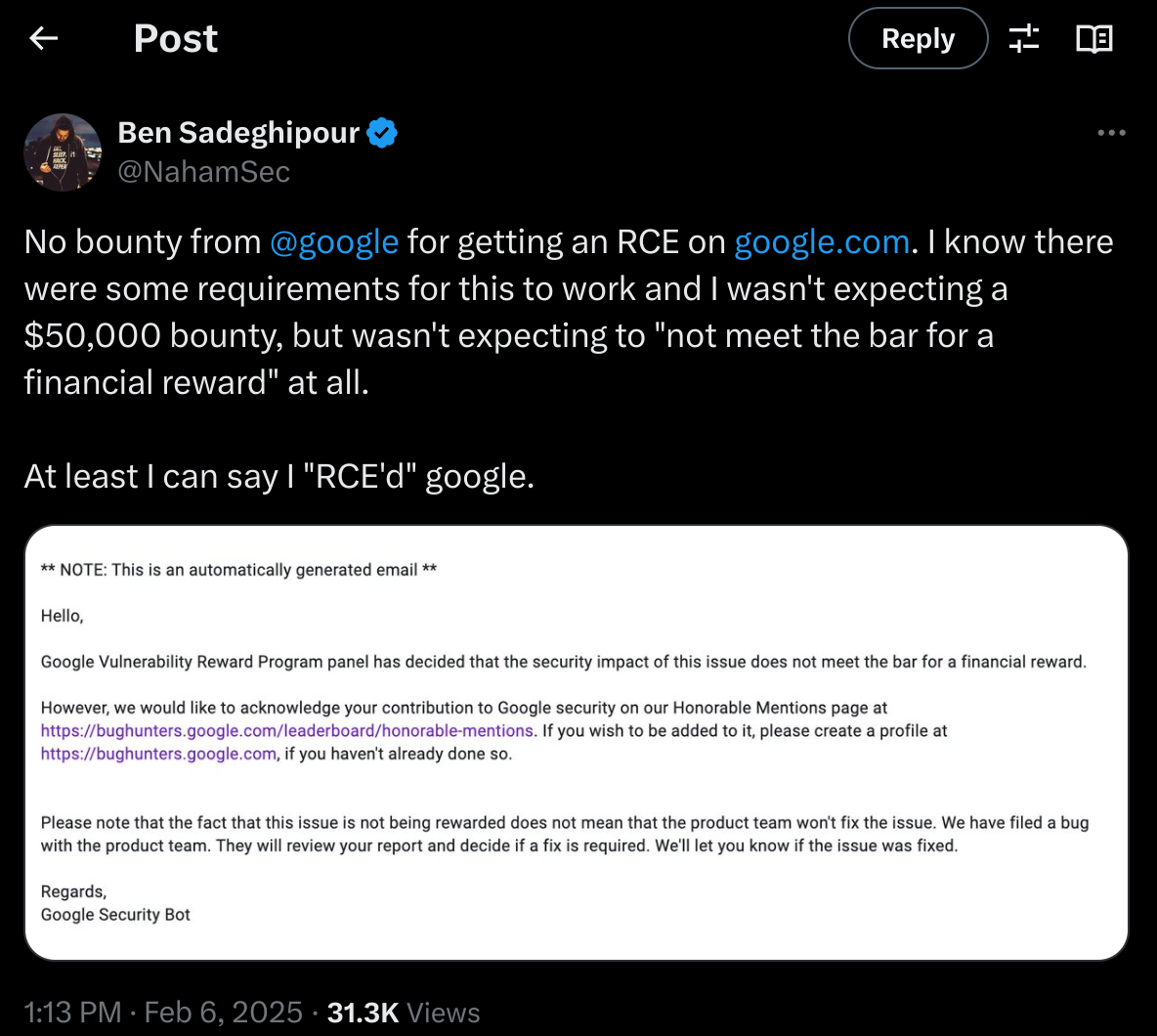

Situations like this are not uncommon in the bug bounty world. I know plenty of bug bounty hunters—many of them my friends—who have reported very cool vulnerabilities, only to have them marked as invalid. Most recently, it happened to a popular security researcher whom I follow and admire, and from whose content I’ve learned a lot. Honestly, seeing that he didn’t receive a reward made me sad. However, setting my personal feelings aside, I’m writing this to capture some of my thoughts and conversations I’ve had with my bug bounty friends in the past.

Bug Bounty

When it comes to bug bounty programs, bug bounty hunters, and the enterprise, I’ve observed a disconnect among all three. I used to do some bug bounty work in the past, and I now work full-time on the enterprise security side. Over time, I’ve seen many instances where a bounty hunter reports complex vulnerabilities to a company, only to have them ultimately grouped under won’t fix, dismissed outright, or accepted without any payout. I often wondered why this happens. Is it because the company is being cheap? Is the vulnerability not “good enough”? Or is there some other reason?

One might argue that it’s unfair not to get paid for producing a tangible result, right? But I believe the crux of the issue is that “results” mean different things to bounty hunters and enterprises. Essentially, what we’re talking about here is “impact.” The enterprise and the bounty hunter often have different perceptions of the impact of a reported vulnerability.

Working on the enterprise side, I’ve seen many assets vulnerable to severe issues like SQL injection or remote code execution. Surprisingly, even these vulnerabilities may not be prioritized for remediation. Why? Because, from the enterprise’s perspective, there was no real impact on the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of user data, nor any significant impact on business operations. That leads me to another key point: enterprises don’t fix vulnerabilities simply because they exist; they remediate vulnerabilities on high-value assets.

In simpler terms, enterprises look at the value of the asset and the cost of protecting it. If fixing a vulnerability costs more than the asset is worth—or if the vulnerability poses no real threat—they may decide not to invest the resources. Of course, financial factors aren’t the only considerations; security risk, reputational risk, and compliance requirements also come into play. However, in every situation I’ve seen where a company refuses to pay a bounty, it’s because they don’t perceive any real impact. Common examples include vulnerabilities found on testing environments, products that are deprecated or unused, or products that no one actually maintains. In such cases, the vulnerability might be valid, but it isn’t a business priority, and the company won’t invest in patching it—let alone pay a bounty.

What does this mean for bounty hunters?

My goal here isn’t to discourage anyone from participating in bug bounty programs. Instead, consider this friendly advice to focus your efforts on popular products, widely used technologies, or anything critical to the company’s core operations. Make sure you can demonstrate how the vulnerability impacts user data, reputation, compliance, or the continuity of the business. If you can clearly articulate that impact, you’re far more likely to get the attention—and the payout—you deserve.

Happy hacking!